I’m not jumping into any of Ellul’s works yet. And there are reasons. First, I still don’t know where quite to start. I hope to figure that out in an essay or two. I keep running into the same problem of thinking I need to read more Ellul before I start writing about him. It’s not a bad hesitation to have, even though I’ve been reading his works for twenty years.

But, as I suppose is the case for all work that is worth anything, you have to start somewhere, which might as well be here. It would be easier if friends didn’t keep recommending to me Ellul’s works that I haven’t read. For example, in the past week I’ve picked up Violence and Presence of the Kingdom. But as I’m not writing a dissertation, I suppose I can get over my ignorance anxiety and just start writing. After all, Ellul helped me as a young pastor, before I had even finished reading the first work of his that I picked up—The Technological Society. Maybe (hopefully) the same will be true for you, dear reader. But the second reason for hesitating jumping into one of his works is that I’ve learned a bit along the way of how to approach all of his works. That thought was behind how I chose to start this series. And that thought is behind I’m continuing it here.

From my title, you’ll pick up on my intent to draw some parallels between Ellul’s work and the movie The Matrix. I’m not the first to draw this parallel and I probably won’t be the last. Two caveats are in order. I have no idea if the Wachowski brothers1 had Ellul’s technical system in mind when they wrote The Matrix (I’m guessing they didn’t). Whether they did or not, it is an apt metaphor for coming to terms with and seeking to undermine an enslaving human system that the majority of folks are blind to. I’m sure The Matrix will continue to be used to illustrate all such systems, real or imagined. The movie really is that good (at least the first one). And to reference an infinitely more reliable source, the Bible talks about this idea of an enslaving ideology believed by a populous. In the Old Testament, the (unplugged) people of God, freed form their slavery in Egypt are repeatedly tempted and tempt one another to return to Egypt, suggesting their former slavery was better than their new found freedom. God warns them against it, and when they try to return to Egypt it goes predictably poorly for them. And into the New Testament, Paul especially warns Christians to be aware of and resist worldly thinking, to which they used to be in subjection, worldly thinking which still had (and has) the ability to enslave them once again. So, whether or not the authorial intent behind The Matrix was meant for this application, the broad illustrative themes are apropos and biblical.

But secondly, and with less import, I’m always reluctant to quote from a movie, and not just because Ellul taught me to be wary of the propagandist nature of the entertainment industry. Movies do seem to me to be pedestrian modes of communication. I’d much rather quote from a book, preferably a book more than 100 years old. But the illustration I’m drawing on here is helpful enough to overcome my fear that I might be something to similar to finding “six Christian themes in Disney’s Frozen.” So if you share my sensibilities about not quoting movies when you’re attempting to do serious writing, I hope you’ll trust me and be patient with me.

Joseph Campbell was the first to document “the hero’s journey.” The hero journey is a rough template describing most heroic stories, both modern and classical. It’s used today to draft story lines for most of the popular movies you’ll watch. According to the template, the would-be hero begins his hero’s journey and experiences and demoralizing failure. Then the hero meets a mentor-guide. The role of the mentor is to teach or challenge the hero to become the hero the protagonist needs to be to triumph in the story. The guide is essential to showing the hero how to overcome whatever is holding the hero back from reaching his hero potential. Famous mentor-guides would include Ben Kenobi, Yoda, Aragorn, Gandalf, Mr. Miagi, and Master Shifu. In The Matrix, Morpheus is the mentor of the hero’s journey. He serves the narrative role of helping Neo become the savior of the human race, ultimately destroying the matrix that enslaves them. Using The Matrix as a rough description of the technological society, Morpheus can serve us as an example of how to engage in our modern world, thoroughly in the grips of technical thinking. And we can draw four conclusions from what I’m calling the Morpheus Principle.

Four Conclusions

First, Morpheus is highly capable inside the matrix. This helps us avoid complete non-engagement. The Amish option is not an option; it is admitting defeat before it has happened. Inside the matrix, Morpheus is knowledgeable and formidable. He understands how the matrix works. He can get into and out on his own terms. He knows the threat posed by agents. And if he meets an agent, he knows how to stay alive (run). For our purposes, we should pursue the same skills. We need to know how the technical system works. We need to know how to use technology adeptly for godly means and in godly ways. Technology will always bring benefits and curses. As much as we can, we must maximize the benefits and minimize the curses. We need to know the risks and how to stay alive, how to preserve our humanity the best we can. For example, digital publishing and online communication are used for all kinds of nefarious ends. But we can also publish truth, in accord with God’s Word, and communicate with trusted friends. I’m currently writing this on Substack—a tool of mass communication, a part of the technical system, and susceptible to propaganda. But what I’m writing should also lead to undermine how far and how much the technical system can exert influence. It is also a type of insurgency. And it’s necessary given what I have to work with. I could get your mailing address (somehow) and send you a newsletter. But that would still be a part of the technological system. Remember we can’t avoid it; this is water.

But we can learn to be adept inside it, like Morpheus.

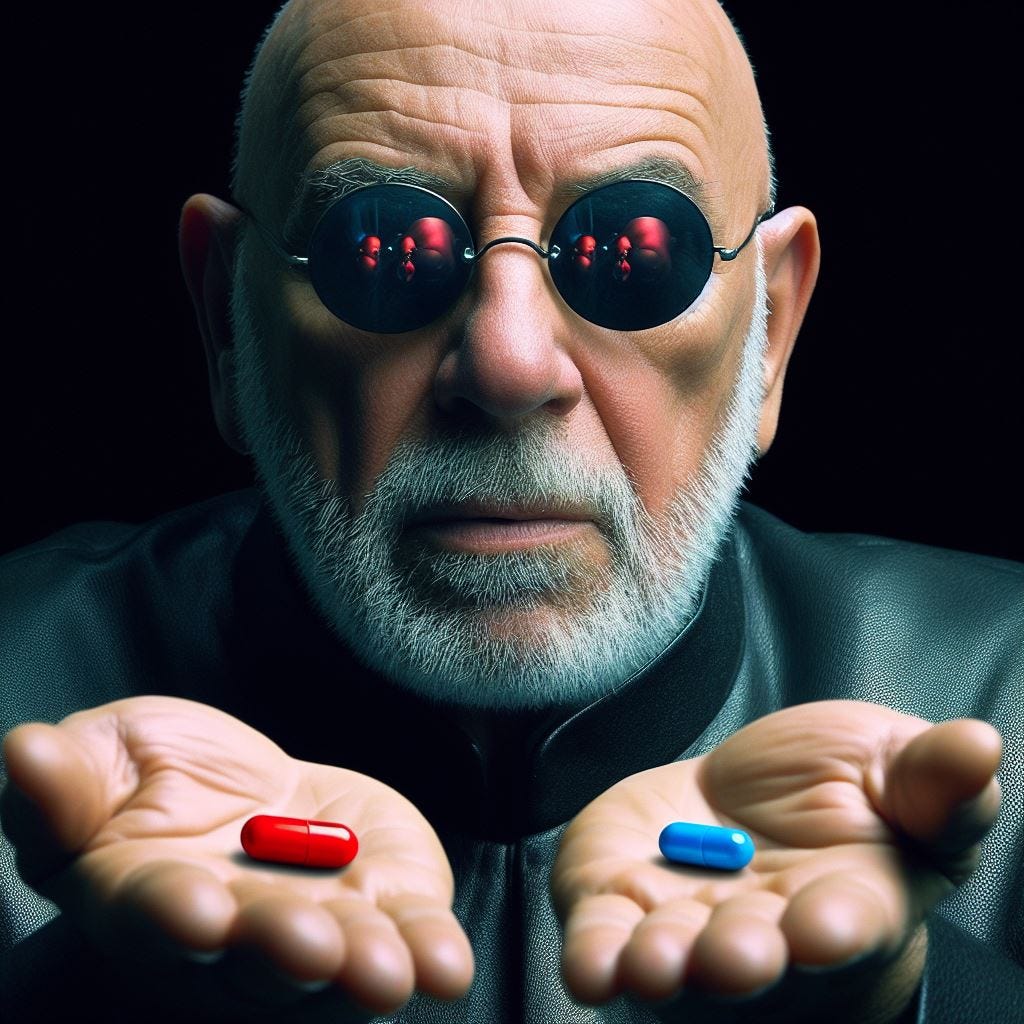

Second, and related, Morpheus is trying to unplug people from the matrix, people who are ready to be unplugged. You probably remember the famous red–blue pill question choice that Morpheus offers to Neo. It’s from this illustration that we get all the multi-colored pill references on social media. In the same way, we have the opportunity to wake people up to how our world really works—to unplug them. You might be able to do this in ways unmediated by machines and technology (and politics). But too much of our social lives are tied up into online communication to miss the opportunity to engage interested people about how the technological system is negatively impacting their lives. Who knows, maybe they’ll take the red pill.

Third, Morpheus was strongly messianic. A key part of the story line is that Morpheus knows he is not the savior, but he knows there is a savior and he’s looking for him. The technical system offers people a type of self-salvation through rationalism, progress, technological advancement, and technological self-augmentation. But it is a false gospel and a cruel god. There is a savior and his name is Jesus. If we are going to engage the technological system and its false ideology—its technical bluff—we must be a messianic people with a mighty Savior-King, Jesus. This is why I believe that Christians must engage on this issue. We are the only people with the power to resist and Jesus is the one who will ultimately win, the only one who can actually provide the salvation that people are looking for in the technological system. This is also what agree with James Poulos that confronting the technological system and the administrative state is fundamentally a spiritual issue.

Fourth, desire a different world. Morpheus isn’t trying to reform the matrix, he is trying to destroy it and return to the world that was destroyed when men and machines underwent a global war. This is important. We aren’t techno-optimists. We believe that the deleterious effects of the technological system will not result in a utopia. The gilded promises of technological progress are a dystopian nightmare in drag. We have to believe this at our core. I don’t know what the new world will be. It won’t be a return to the 1950s or to colonial America. It will be something different. We will be colonists again. But all of this starts with a desire for a new world, a different world than what the technological system promises.

These are just four conclusions, there are probably others. And I hope you see how Morpheus serves as a fictional example of how to engage with a technological system increasingly opposed to biblical anthropology.

Both brothers now identify as women. It is somewhat ironic that The Matrix could have been written about transgenderism but is now, at least in its red-blue pill metaphor, used by online conservatives.

I really liked your Morpheus principles. They are especially effective as a person can remember the vividness of the story in order to recall these truths. One aspect I have learned from Substack is that writers tend to present their main points initially in order to keep readers who might otherwise move to other stacks. I might suggest starting with your main idea or a bulllet point list of what will follow. It’s a different format than a sermon that would allow a writer to have that meta dialogue with the audience at first. Just a suggestion.